Between October 2021 and February 2022, we randomly allocated our 30 consenting, eligible participants to the three groups of the study. After randomisation, there were six patients in the Usual Care (UC) group, and 12 each in the Acupuncture and Nutritional Therapy (NT) group. That’s a 2:2:1 allocation ratio between the groups, meaning that for every one person in the Usual Care group, there were two in each of the Acupuncture and NT groups. That ratio is slightly unusual in trials, and we did it because we have two therapy groups that we want to compare with each other.

To explain: a future trial will work out whether the therapies are effective by comparing the average post-therapy scores of each intervention group (i.e., acupuncture and NT) with the average post-therapy score of the Usual Care group; if there’s a statistically significant positive difference between the UC group and the Acupuncture group, the trial will conclude that acupuncture, when added to their usual care, offers benefit to people with AF. The same goes for NT: if there’s a positive difference between the UC group and the NT group, the trial will conclude that NT offers benefit for people with AF.

So far, so standard. But if we want to work out which of the two therapies is best for AF (relative to each other) we need to compare the post-therapy scores of the acupuncture group with the post-therapy scores of the NT group. And in any comparison between the acupuncture and the NT group, we would expect the average post-therapy score difference to be smaller than the average post-therapy score difference in the comparison between either of those groups and the Usual Care group. That’s simply because both groups have had some treatment in addition to their usual care, so both groups can reasonably be expected to have improved somewhat, making the differences between them smaller.

In a trial, the smaller the average difference between any two groups, the harder it is to detect reliably. To combat this, we add more people to the trial (also known as “increasing the trial’s power”). In the case of a trial with three groups, we would “add” more people simply by increasing the numbers of people in the intervention groups relative to the numbers in the usual care group. That means we can be reasonably sure that, in a future trial, a difference between the acupuncture and the NT groups would be reliable, and not just due to chance.

Feasibility versus effectiveness

But hang on a minute, this is a feasibility study, right? We’re not actually looking to calculate the differences between the groups. That calculation would be about effectiveness, whereas all we’re doing in this feasibility study is looking at – well, feasibility! So why do we need to use that 2:2:1 allocation ratio in the first place?

Good question – and it applies to all aspects of the feasibility study design!

If a future trial will be using a 2:2:1 allocation ratio (or any other design feature), it makes sense to use that ratio also in the feasibility study to avoid introducing a variation between the feasibility study and the future trial, so we can be reasonably sure that our feasibility results will apply (“be generalisable to”) a future trial. Let’s say, for instance, that we don’t know what kind of effect the 2:2:1 allocation ratio has on, say, recruitment. It’s easy to imagine that somebody who wants to have some acupuncture or nutritional therapy for their AF might want to join a trial where they have a 4 in 5 (80%) chance of getting either acupuncture or nutritional therapy (as they would with our 2:2:1 allocation ratio). But if we used this ratio in the feasibility study, but then changed it for a future trial (say, to make it a more usual 1:1:1 so equal numbers of participants would be allocated to each group), that would give people with AF a 2 in 3 (66%) chance of having either acupuncture or nutritional therapy, and the odds of receiving some kind of therapy would be reduced. That might deter some people from taking part, compared with a feasibility study offering an 80% chance; and if we’d calculated the likely rate of recruitment in a future trial based on the numbers of people that signed up to the feasibility study, we could find that it takes longer to recruit than planned (which takes extra money and time) or even that we can’t recruit the number of people we need (which makes the trial much less valuable since it wouldn’t be sufficiently powered to produce reliable results).

In other words, if we changed the allocation ratio between the feasibility study and the trial, we automatically have more uncertainty about recruitment relating to allocation ratios – or to put it the other way round, we can be more certain to reliably predict the recruitment levels in a future trial if we keep the same allocation ratio in both the feasibility study and the future trial. So that’s why we try to keep the design of a feasibility study as close as possible to the design of a future trial, whether that’s the allocation ratio or the eligibility criteria or the assessment processes or… whatever!

The randomisation magic

In Santé-AF, we randomly allocated people to the groups. Randomisation is a very special thing in trials because it allows (in theory) the balancing of all the known factors and the unknown factors that might influence people’s response to treatment. Based on the soundness of the randomisation, we can determine causality – in other words, the causal link between the treatment received and any improvement (or worsening) of the condition. It’s this that allows us to say, at the end of a decently-designed and conducted trial, that a given treatment is effective (or not effective, or even harmful) for a given condition.

Well… of course it’s not that simple, and there is a lot of variation on the theme of randomisation, but that’s the basic principle. For more detail, and for a look at some of the strengths and weaknesses of various flavours of randomisation, I recommend David and Carole Torgerson’s book Designing Randomised Trials in Health, Education and the Social Sciences: An Introduction, published by Palgrave Macmillan.

For Santé-AF we added an extra random element, known as “blocking”; basically this meant we allocated people to groups using blocks of 5 and 10 participants, with the blocks themselves being randomly applied to make sure that we couldn’t predict which group a given participant was going to end up in. The actual randomisation itself was done using the Sealed Envelope randomisation engine – a fantastic service, available to any researcher at a very minimal cost. Basically, the participant’s Study ID number is fed into the randomisation engine, which randomly allocates the participant to a group and sends the researcher an email to confirm that allocation. Combined with the blocking, using the Sealed Envelope service meant that we (as researchers) couldn’t influence the trial’s results by, say, putting into a given group only those people we thought might do well in that group, or people who we thought might want to be in that group. Either of those things would mean the study’s findings wouldn’t be reliable.

The service is called Sealed Envelope because in the past, researchers used to randomly allocate participants to groups using actual physical sealed envelopes – a process that was vulnerable to subversion, where researchers steamed the envelopes open, or changed their order, and so on, to make sure that people went into the groups that the researchers thought they ought to be in, or thought they’d like to be in, and so on. This obviously made trials less than reliable, since their results didn’t prove the effectiveness (or not) of a given treatment – instead, all they demonstrated was whether the researchers believed that a given treatment was effective or not! The Torgersons’ book contains some horror stories about this kind of practice – some are hilarious, while others are truly shocking and resulted in actual participant deaths. If you’re interested in how trials are carried out, I recommend it.

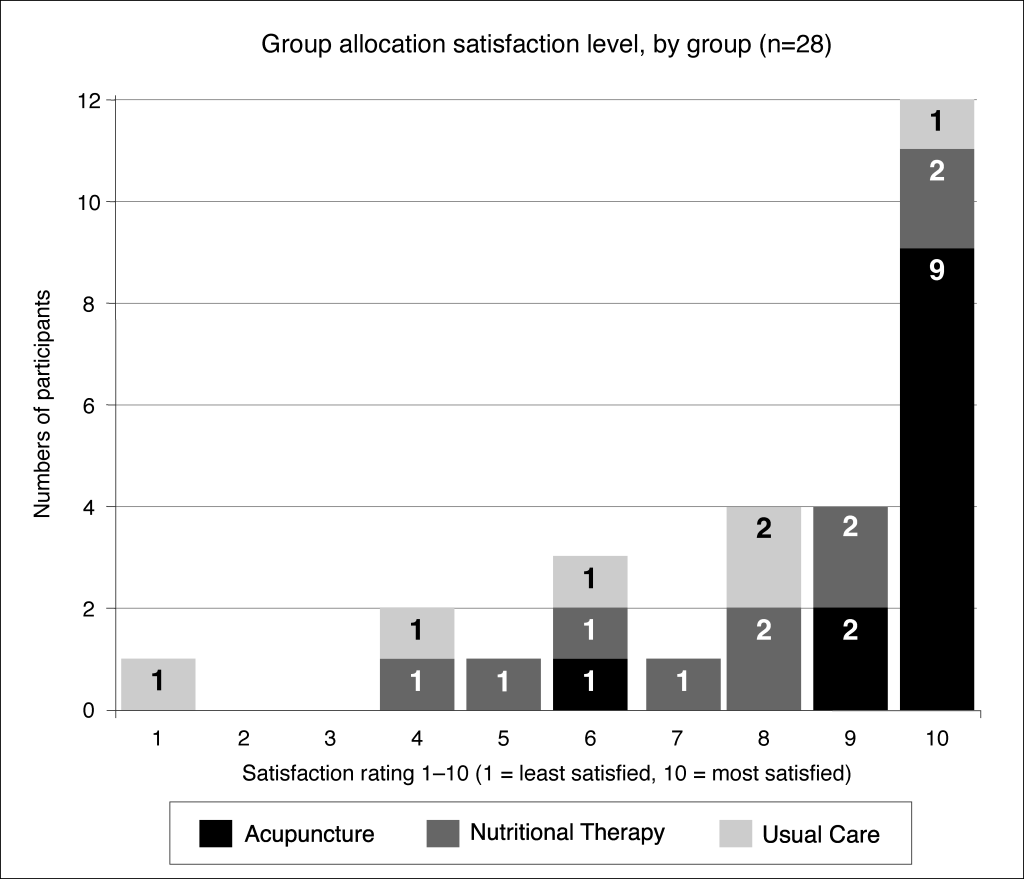

Back to Santé-AF! After each person was randomised, we let them know by email and letter what group they were in. Once they’d received this notification, we asked them (by automatic poll on their mobile phone) how happy they were to be in their group (scale of 1-10, higher numbers = happier). Twenty-eight people responded to the poll (one person had dropped out after being randomised, and one person didn’t respond to the poll).

What did the poll data tell us?

The poll data was interesting. As you can see in the diagram, most people were happy with their group, but there were a few people who weren’t pleased. By asking questions in their study assessments, we found out the two main reasons for unhappiness with their group allocation: first, because they’d wanted to have some therapy (and they didn’t mind which therapy); or second, because they’d wanted to be in another group (usually they were in the NT group and wanted to be in the Acupuncture group).

We collected this data firstly to find out if it was feasible to collect it (which sounds a bit circular, but that’s what a feasibility study does) and secondly to help us decide whether to allow people to choose their group in a future trial. Allowing participants to choose their treatment is a contentious issue in trials because it negates a lot of the benefit of randomisation – but if a lot of people were unhappy about their group it could be worth thinking about a so-called “preference” trial to ensure that they would continue and complete the course of treatment in a future trial. Actually, what the poll showed was that most people were happy to be in their group.